Deconstruction of self with Nicholas Albrecht

This article contains image descriptions in the captions to help those with visual impairments.

The title of Nicholas Albrecht’s first monograph has been respectfully poached from the 1926 novel of the same name by Italian writer Luigi Pirandello. In it, Pirandello (1926) elaborated about the decomposition of life and the deconstruction of the self through his central character Vitangelo (whose name can be translated as ‘life of an Angel’). After being led to the edge of madness Vitangelo finally arrives at a state of inner peace, no longer desiring anything and endeavouring to follow life moment by moment with no history or past to weigh him down.

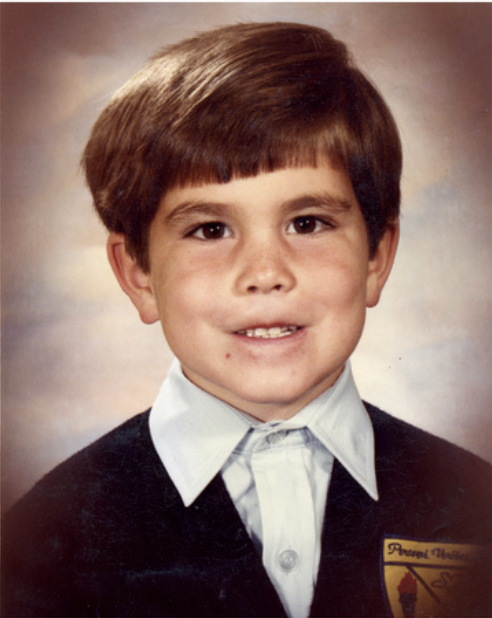

The initial heavily vignetted photograph of a young boy posing in his school uniform alerts us to the possibility of a work centred on the idea of identity. The clear lack of a school tie and tightly collared shirt suggests a constrictive lack of care, or perhaps poverty. Is this the forced smile of the author, a found image or an early snap of his Salton Sea subjects? Having spent three months getting to know the community before he started to photograph has resulted in some tentative and respectful portraits. This is the respect of an outsider whose place in the community is new and uncertain.

In effect Albrecht is presenting to us the result of an organic process. The fictional essay that acts as a forward and introduction to the book follows and summarises, what we must assume is Albrecht’s introduction to Salton Sea and his subsequent 10 month stay there. The story an he read as a subtext to the images as it eloquently seeks to extrapolate from the chaotic flow of photographs a narrative of Albrecht’s experiences.

This is quite useful as the various visual styles, consisting of intentionally constructed scenes, composted portraits, documentary and tonal landscape studies, initially confuse the senses as we struggle to find a place to situate Albrecht’s work. This ambiguity only adds to the unsettling nature of the disparate and chaotic flow of content that appears more like a visual puzzle we are being challenged to solve.

There is also an unsettling psychological tension to the work that hints at an implied violence. Absence and silence permeate the pages giving the work a sense of uncertainty and mystery. The double spread of impenetrable black hills set against a dark blue starless night sky informs us of the solitary nature of the desert, a place devoid of the extraneous. Here there are only the hopes of a young girl pinned to the wall as a statement of intent, harshly lit by desert sun; here the vegetation looms like a crazed animal as the landscape conspires to engulf you in its moisture bereft soil; here are only flies, snakes, insanity and death, and a community held together by God and the threads of shred experience.

Albrecht seeks to break down the superficial and familiar through presenting his narrative as a series of seemingly dislocated images. In contrast to Vitangelo chasing his true self through reason alone, Albrecht hints at the absurdity of constructing an idea of place through obvious or over representation and presents the liberating irrationalism of his narrative as an antidote to reason and a guide to the unravelling of self. Recall the young boy confined in a tie-less school uniform compared to the final image: a brooding young teen, bare-chested and psychologically dark but stripped of pretence and captured in the hard contrast of harsh desert window light. The filters of our pre-conditioned selves, in some way like the window blind, no longer act to prevent the revealing of the true, and somewhat terrifying, raw inner self.

Albrecht’s work impels you to look again as, like a mirage, the images ebb and flow, sometimes obvious, sometimes not, weaving together a narrative of tension of place and belonging, of isolation and emptiness, of ordinary lives bleached bare by the scorched and hostile landscape. These images are arranged to cut through falsely reassuring outer appearances to reveal a more internal and disquieting process of self-withdrawal and the questioning of identity and place. Compared to the ubiquitous and cliched arty snaps of water engulfed telegraph poles and aesthetic decaying trailer homes, Salton Sea has never looked so interesting.

Nicholas Albrecht: One No One and One Hundred Thousand

Printed by Schilt Publishing

ISBN: 9789053308219

19X24cm Hardcover 84 pages

£35

Volume Seven: Analysing the Evidence