In conversation with Anthony Luvera

This article contains image descriptions in the captions to help those with visual impairments.

“I’m interested in how when an individual or a community is able to represent themselves, the stories they have to share can shake up preconceptions and open up new information about their lives than can be observed by an outsider looking in.”

One of the important roles within photography is being a representative and visual voice for your subject. However, this can sometimes travel a very fine line between exploitation and representation. Anthony Luvera’s practice, on the other hand, demonstrates the representative abilities of photography. Giving autonomy to his subjects, he acts not only as a photographer, but a facilitator and collaborator. Working with his subjects in creating a self-representation that honours, and gives a three dimensional look at who they are, Luvera’s work has positively utilised the photographic medium, bringing attention to various issues and communities, including homelessness and the LGBT+ community.

Luvera is also recognised for how he documents his projects, highlighting how the research and development stages of a project are more than just background work, and are equally important as - or arguably, more than - the final outcome images. So much so, that the process becomes a vital component of the final body of work, as is evident in Residency, Assembly and Not Going Shopping, to name a few. This documentation gives a real insight into what Luvera and his collaborators explore, giving the viewer a rare and privileged look at more than just the “surface” of the project. “The process of a participatory project or a socially engaged practice, is as important, if not more so, than the finished pieces presented to an audience.”

I caught up with Anthony to dive into representation within collaborative practice, and get an exclusive look at his latest project made in collaboration with Sarah Cromie, She / Her / Hers / Herself. Described as “an evolving portrait of an individual’s experience of gender transition”, it was due to be exhibited at Belfast Exposed in April and May of this year (2020), but like many, was unfortunately put on hold due to the CoronaVirus pandemic, and we look forward to seeing the full project exhibited in 2021.

Alice Turrell (AT): From your body of work Not Going Shopping, to the Young People's Guide to Self-Portraiture for National Portrait Gallery, to your role as a photography educator, you clearly have a passion for facilitating the creative expression of others and collaborating in your work. When and how did you first get interested in this form of photography?

Anthony Luvera (AL): My practice took a collaborative turn in 2002. I was invited by Crisis, the charity for people experiencing homelessness, to photograph at their annual shelter event over the Christmas period. I declined the invitation saying something about preferring to see what the people I met would take photos of. A short time after this I was doing some consultation work for Kodak on their single use cameras, and I found myself in a position to access a large donation of cameras and processing vouchers. I went back to Crisis and proposed to create a project in their activity centre, Crisis Skylight. It became clear to me that a straight documentary approach wasn’t the only way to tell other people’s stories using photography. Alongside developing this project, I continued to teach photography and facilitate community programmes for community photography projects, museums, galleries and cultural spaces.

AT: Your work often highlights issues and subjects within communities, for example Assembly which is a collaboration with people who have experienced homelessness which was recently exhibited as part of Taking Place, at London’s The Gallery at Foyles. Why is it so vital for communities to be given the chance and space to represent themselves and have their work seen rather than a photographer fully taking charge?

AL: I think one of the wonderful things about photography is the many different kinds of ways the medium can be used to speak about the world. Early on, when working with people experiencing homelessness, and other groups of people from marginalised or overly-spoken for backgrounds – such as children from lower socio-economic households, people with mental health issues – I quickly realised that their experiences and the things they were interested in saying about their lives were much more interesting, nuanced and enlightening than the stories I could convey on my own. Even when a photographer fully takes charge, as you say, their work is still contingent on a range of contributions by other people – subjects, assistants, technicians, friends and colleagues – and usually this input is hidden and goes unacknowledged. I’m interested in how when an individual or a community is able to represent themselves, the stories they have to share can shake up preconceptions and open up new information about their lives than can be observed by an outsider looking in.

AT: That is a really interesting point to make, there are so many people who are often overlooked who’s work goes into any project other than the photographer. When it comes to starting up a new collaborative project, what is your initial approach like? Do you find people are quite open and welcoming or cautious?

AL: When starting a new project, there will always be a number of practical considerations to work with, in relation to things like budgets, resources, and timing. There also will be the agenda of the commissioners, funding bodies and partner organisations to take on board. I think it’s important to have a clear understanding of how these factors will play a part in how I determine the way I conceive the invitation I present to participants. For example, when beginning a project with people experiencing homelessness in Birmingham, I spent around a year or so getting to know the staff and individuals associated with SIFA Fireside, a charity for people experiencing homelessness, before inviting participants to use equipment with me. One of the ways I approach this is to spend time volunteering within the organisation, meeting as many people as I can, and having informal conversations about my plans. You might say this is a kind of consultation. It’s a really useful way for me to find out about how people feel about what I hope to do and to find out the best way to go about it. Some people are curious and enthusiastic, others are not interested, but there’s never any point trying to convince someone to be involved in a project.

AT: Your process and approach seems really considerate, with you flexible and moulding to what you learn from getting to know the participants and situation better. Really letting them guide you in a way. Do you ever feel that when facilitating people's creativity there is a danger of it becoming exploitative? Or see it in the work of others? If so, how do you avoid this?

AL: These are really interesting questions you ask. They strike at the ethics of a collaborative practice. I think it’s important to be as clear as you possibly can about the invitation you’re asking people to take part in and to share as much information you have about your intentions, the conversations you have with individuals and organisations that commission, fund or otherwise support the creation of the work, and decisions you make about its realisation and presentation. I think often there can be a misconception that if a project is collaborative, participatory or co-produced in some way, this a good thing in itself. However, it seems to me that questions ought to be asked about the intentions of the artist; the intentions of the participants; and how the power balance of their engagement plays out in the process of making the work.

AT: Both photographers and audiences can have a tendency to focus on the finished project, the end result, and gloss over the process and journey to get to final pieces. Arguably - especially in participatory projects - the process is more important. What is your stance on this view? And if in agreement, how do you make sure the process is seen?

AL: I entirely agree with you. The process of a participatory project or a socially engaged practice is as important, if not more so, than the finished pieces presented to an audience. Over time, I came to realise this through my practice and have attempted to represent this in a number of ways. In Residency I included the Polaroids from the creation of the Assisted Self-Portraits and documentation of the participants and me working with each other, alongside the photographs and Assisted Self-Portraits we made. In Assembly, I included screen grabs from the software we used with a laptop tethered to the camera equipment, and audio recordings of conversations between the participants and me when making and editing the work. In other projects such as Not Going Shopping and Let Us Eat Cake, the participants and I created blogs throughout the making of the work. I think it’s interesting to find ways to enable participants to be part of the recording of the process using various kinds of media, so that it’s not just me doing the telling of what happened and how it happened.

AT: Your work demonstrates perfectly how photography can be a catalyst for social change and awareness. Did it take a lot of experimentation, trial and error to find what works best for you?

AL: I’ve been working in ways described as collaborative, participatory or socially engaged for eighteen years now, and I have learnt a lot about collaboration through each project. And each project informs the next. In this sense, my practice has been an ongoing experiment of trial and error, and I think this is what keeps me interested in working in the way that I do.

AT: What advice would you have for photographers interested in pursuing collaborative and participatory bodies of work?

AT: Listen carefully to the people you work with. Ask questions about what you hope to do with participants, and take on board their answers. Find ways to share decision making with participants. The most important part of any collaborative or participatory body of work, is the relationships you develop with participants and the trust that will hopefully emerge through this. This can’t be faked – certainly it shouldn’t be – and often this takes much more time than you expect. But it can sometimes take you down a different creative path to the one you expected, and this can be an exciting way to learn more about the people you work with, yourself, and your practice.

I also think it’s important to be aware of other artists and researchers who also explore collaboration and participation, and not just in photography. Get to know about who else is working in this way today and to find out about practices of the past. From the 1970s to the 1990s, photography projects carried out by many individuals and organisations across the country are described as being part of the community photography movement or involving collaboration in many different kinds of ways. Just a few of these people include Jo Spence, Rosy Martin, Judy Harrison, Paul Carter, Andrew Dewdney and Martin Lister. Their practices and writings, and the work of many others, is a rich seam of learning and inspiration to draw from. This is one of the reasons I set up Photography For Whom?. The periodical looks seeks to shine a spotlight on the important yet overlooked work that was done in the past and to generate critical discourse about contemporary practice.

AT: As an educator, what do you look for most in projects? What, in your eyes, makes a body of work stand out?

AL: Commitment by the artist to developing the technical, aesthetic, conceptual and ethical basis of the work. This process is often called research, but really it’s a process of experimentation, reading, thinking, and trying things out. It seems to me, even with the apparently simplest idea, when all of these elements are in sync a body of work will stand out.

AT: Are there any up and coming artists or projects you think we should be keeping an eye on?

AL: There are so many. A few that immediately spring to my mind, including Arpita Shah, Maryama Wahid, and Nilupa Yasmin. Their work was exhibited in the group exhibition Too Rich a Soil, curated by Nicola Shipley, at the New Art Gallery Walsall earlier this year. I really appreciate how each of these artists, in different ways, explores cultural identity and celebrates the roles of women in their families and communities. The work of Dawinder Bansal also made an impression on me recently. I saw her video work Asian Women & Cars: Road to Independence at the Blast! Festival in 2019. It’s a marvellous composition of oral histories, film, photographs and sound that tells the stories about the relationships between South Asian women living in Sandwell and the Black Country, driving, and their cars. It’s a thoughtful piece about cultural identity, patriarchy, and independence.

AT: Could you tell us about your exciting latest body of work that was meant to be shown in Belfast recently but was placed on hold due to the pandemic?

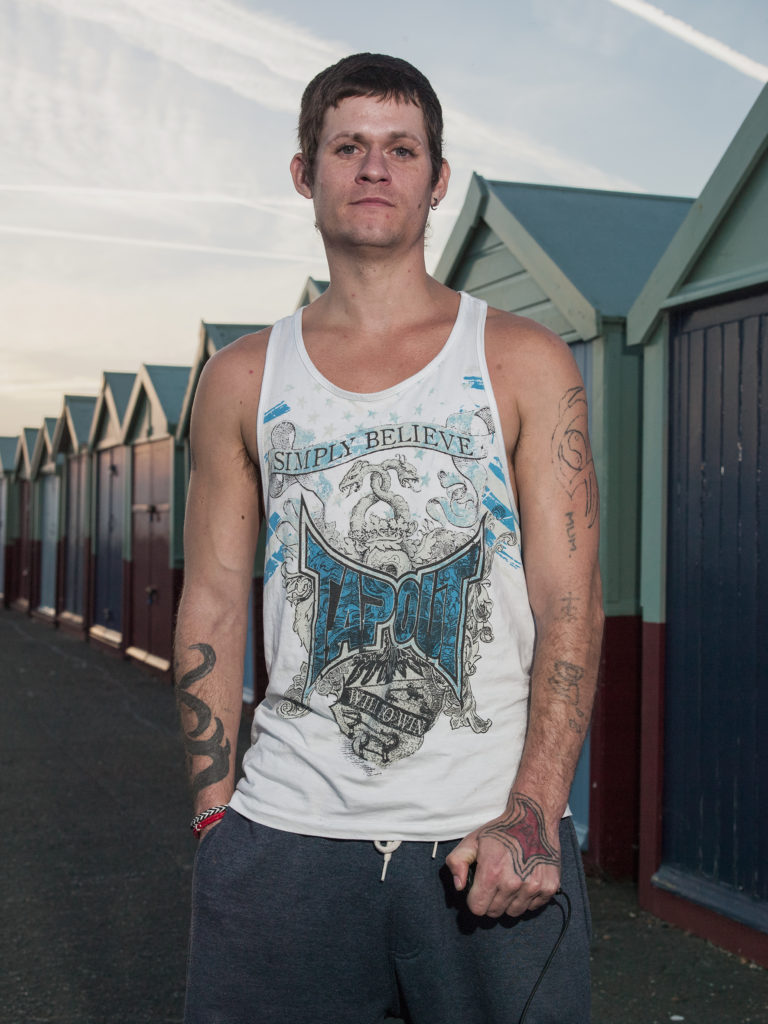

This project is called She / Her / Hers / Herself and is made in collaboration with Sarah Cromie. I first met Sarah through the making of Let Us Eat Cake, a collaborative body of work made in 2017 with queer people living in Northern Ireland, commissioned by Belfast Exposed and exhibited in their gallery that year. Sarah began to accept her trans identity around this time and when Let Us Eat Cake culminated we continued to work together. She / Her / Hers / Herself is comprised of a mixture of elements including images made by Sarah on her mobile phone, and photographs and video we create together. It is an evolving portrait of an individual’s experience of gender transition, the expression of femininity, and the broader changes taking place in Sarah’s life as she establishes a new career as a beautician. An exhibition was scheduled to take place at Belfast Exposed in April and May this year but has been postponed. We are now looking at some time in 2021.

AT: What is next for you and your practice?

I’m continuing to develop She / Her / Hers / Herself with Sarah. I’ve also been working on the new issue of Photography For Whom?, which will be out within the next month. And we have some exciting plans for public events and future issues of the periodical. I’m also progressing my work with people experiencing homelessness in Birmingham, commissioned by GRAIN in association with SIFA Fireside. I’m just as excited about exploring issues to do with community, collaboration and representation as I was 18 years ago.

You can see more of Anthony’s work at http://www.luvera.com/

Words and Interview by Alice Sophie Turrell

Leave a Reply