Night at the Museum with Klaus Pichler

This article contains image descriptions in the captions to help those with visual impairments.

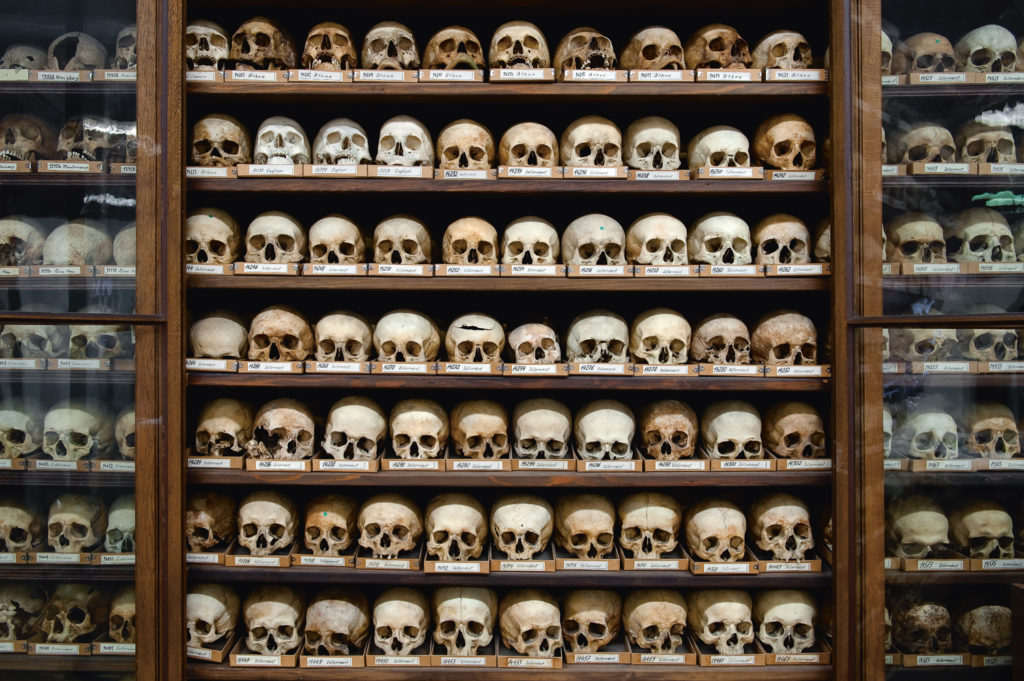

Klaus Pichler’s body of work Skeletons in the Closet opens the doors to the hidden world of the Natural History Museum of Vienna

Catching a glimpse through the basement window of the Natural History Museum of Vienna - a place deeply connected to his childhood - Klaus Pichler got to thinking, what does a museum look like behind the scenes? Where do all the undisplayed exhibits go? This was the spark that ignited his long term project Skeletons in the Closet, documenting the hidden world that spans 45,000 square metres below the Natural History Museum of Vienna.

Through this project, Pichler sees this space as an array of magnificent, otherworldly still lifes that represent not only what lies behind the closed doors of a museum, but how we interact with and view life and death. Pichler’s use of documentary photography on such a fascinating and often unattainable subject matter and location lets you peek through the keyhole of life at the museum. Creating both an inventory and a narrative, but leaving space for the audience's imagination to run wild with possibilities and moments of escapism that transport you. As Pichler so aptly puts, “sometimes not the images are telling the real story, but the gaps between them which everyone has to fill themselves”.

I caught up with Pichler to find out more about how Skeletons in the Closet is a culmination of childhood wonder and curiosity. Delving deeper into the project, discovering that the excitement of endless possibilities when pairing exploration and imagination does not die “this project made me feel like a kid again, curiously wandering through an abandoned house – only this time it was legal”. More than just an exhibition space, the museum is a collection and home for a vast array of once living creatures and artefacts that each have a story worth being shared and brought to life.

The project offers a fascinating, and somewhat humorous, glimpse behind the scenes of a museum which the public don’t get the privilege to see. When exploring behind the scenes, did you stop getting surprised after a while? Or did it continue to surprise through to the end?

Exploring the vast spaces of the museum with my camera has excited, surprised and amused me from the first to the last day. I remember the joyful feeling when I was sitting in the subway on my way to the museum, anticipating what I would encounter in the next hours. Somehow, this project made me feel like a kid again, curiously wandering through an abandoned house – only this time it was legal, the 'house' was a museum filled with stuffed animals and I had my camera to capture my explorations, which really made me feel privileged.

Skeletons-057, Klaus Pichler ID: A sound system sits on top of a shelf with plugs and electrical wires below. Above the sound system is a photograph of an extinct model of a wholly rhino. Next to the sound system on a wooden panel is a taxidermy of a brown owl on a branch, looking past the viewers gaze.

Have you always been interested in museums and natural history, or was this a new area of interest to you?

This particular museum, the Museum of Natural History Vienna, is one of the most important places when it comes to my childhood. Growing up in the countryside, it was a must to visit the museum whenever I have been to Vienna with my family. I have always been interested in natural history and I am sure the museum has played a massive role in shaping my interest for nature, later on leading to my studies of landscape architecture (which have been ultimately stalled by photography).

I still love to go there when I am searching for inspiration – in contrast to art museums where the world is visible through the filter of creative minds, a natural history museum is the unfiltered way of perceiving nature, creation and – in a mirrored way – also society, power and politics.

Do you think you could - or would - revisit and continue the project elsewhere in a different museum, or has it run its course?

I suppose that it probably would be possible to do a project like mine in every natural history museum – especially in the ones which have a long history themselves. Back then the architecture of those museums was built according to different principles than nowadays, where functionality and technical infrastructure are predominant and the collections are organized and arranged in a logistically perfect way. Back then, the historic, representative architecture left plenty of empty corners and 'leftover' spaces, which now are filled with specimens of the collection which is literally bursting at the seams. So I think the principle of specimens involuntarily interacting with the surrounding space is something one can find in almost every museum of this type. For me, the project is a closed chapter, not at least out of sentimental values because of the importance this particular museum has had for my childhood.

How easy was it for you to gain access, and were there a lot of rules and limitations?

At first, it had been kind of a long ride until I found the right person to address with my plans for the project. I had no luck trying it the 'official' way because the responsible persons simply did not understand what I wanted to do, but later I tried it the informal way by contacting scientific staff, until I found one scientist who liked my idea and introduced me to the vice director. Once I had been granted permission and was equipped with the necessary paperwork, it was really easy to gain access to the different departments and collections. More than one time I have been left alone for hours to stroll through the basements and collections. I particularly remember a day in the mammal collection four levels below ground, where I had the opportunity to take photos completely alone for a day – an incredible experience, being locked in a 2.500 square meter room with 400 stuffed animals ranging from mice to elephants.

The images are striking and beautiful, telling a story bringing the exhibits to life. How much input did you have in curating aspects such as lighting and composition, and how did it differ/present new challenges to you other projects? Or did you shoot it exactly as found?

I have always taken the photos of the sceneries as I encountered them and with the available light, my only input was to decide the framing of each image. Besides that, I did not touch anything and left everything unchanged. I thought that it would have been too easy to arrange the images myself, so it was much more thrilling to search for those 'random dioramas'. The museum is constantly changing – specimens are taken from the collections to the exhibition halls or to other museums, and are brought back later, so it was just a matter of time and presence until I found newly arranged sceneries.

Working on this series, I have firstly gotten in contact with a photographic principle which I would consider as one of the most powerful assets of photography or of visual arts in general. I would describe it as '1+1=3' or, in words, 'take two things which have nothing in common, combine them on a picture and see what new meaning you have created'. This simple principle – in my case basements and stuffed animals – is a combination which guarantees surprises, and I have used it in many ways in my later projects.

Now especially, images can be a crucial form of exploration and escapism, which Skeletons in the Closet provides perfectly, offering a world that is often behind closed doors. Allowing viewers to imagine scenarios and stories behind each image. Is this space for imagination incidental, or something you had in mind for the project?

For me, photography is always about storytelling, no matter if it is documentary or conceptual work. Photography is like a keyhole into a room the photographer has designed. Sometimes, photography is even stronger if it leaves room for interpretation, if it is a starting point for possible stories and meanings which are indicated, but not finalized. In other words, sometimes it’s not the images that are telling the real story, but the gaps between them which everyone has to fill themselves. In this project, I have had the privileged situation that although it is documentary photography in its purest form, the contents of the images are seeming surreal and intentionally composed. So my task was to search for sceneries which had a surreal appeal and photograph them in a way that they reveal their story.

Is there a particular image or images that you feel sums up the project and behind the scenes of the Museum of Natural History of Vienna?

I think the image which sums up the project is the one from the mammal collection ('Skeletons-045') which is showing a huge array of animals and therefore seems like an inventory. Especially the way how this compilation of animals is arranged in the most space-saving manner is telling a lot about the nature of museum collections and about the museum as an institution itself. Back then, when the museum was founded, a museum was meant as an institution created for showing and explaining the world – with all its implications. If you look at the heap of animals on the image, one question is predominant: how did those animals find their way into this basement from their habitats all over the world, and, subsequently, why are they here? Especially in post-colonial times, these questions are important ones, and it is an interesting task to dive into the history of a natural museum as an institution.

Personally, now seeing museums I have a new and exciting sense of wonder of what happens behind the scenes because of this project. Do you feel the same way, or have found this to be a common reaction?

Yes, I feel the same way, absolutely. It is also interesting to draw a wider circle and to contemplate the strange presence of life in a natural history museum, although basically a place like that is nothing more than a morgue for animals, dead but on display. Especially when you observe children happily strolling through the museum, you notice that they explore it with a complete absence of death in their perception. So experiencing a natural history museum is not only about the duality of displays and behind the scenes, but ultimately also about life and death.

How would you feel if you were to see the book in similar spaces in the future? Would it seem almost full circle to you, and in a way life imitating art?

Oh, something like that has already happened when my series was exhibited in the natural history museum in 2015. The images were presented on the walls of a 400 square meter space and in the middle of this space some of the specimens which I have photographed (e.g. the basement shark, the non-smoking cobras, the monkey with the mirror) were placed in a way it seemed they were looking at the images. It definitely felt like a closed circle and I loved how these meta-layers added to the project.

You can see more of Klaus’ work at https://klauspichler.net/

Interview by Sophie Turrell