The Sublime Nature of Life and Death with Alan Knox

This article contains image descriptions in the captions to help those with visual impairments.

“I wanted to explore the sublime as the human journey from a primordial object of the universe, to subject on Earth and the return to objecthood in death”

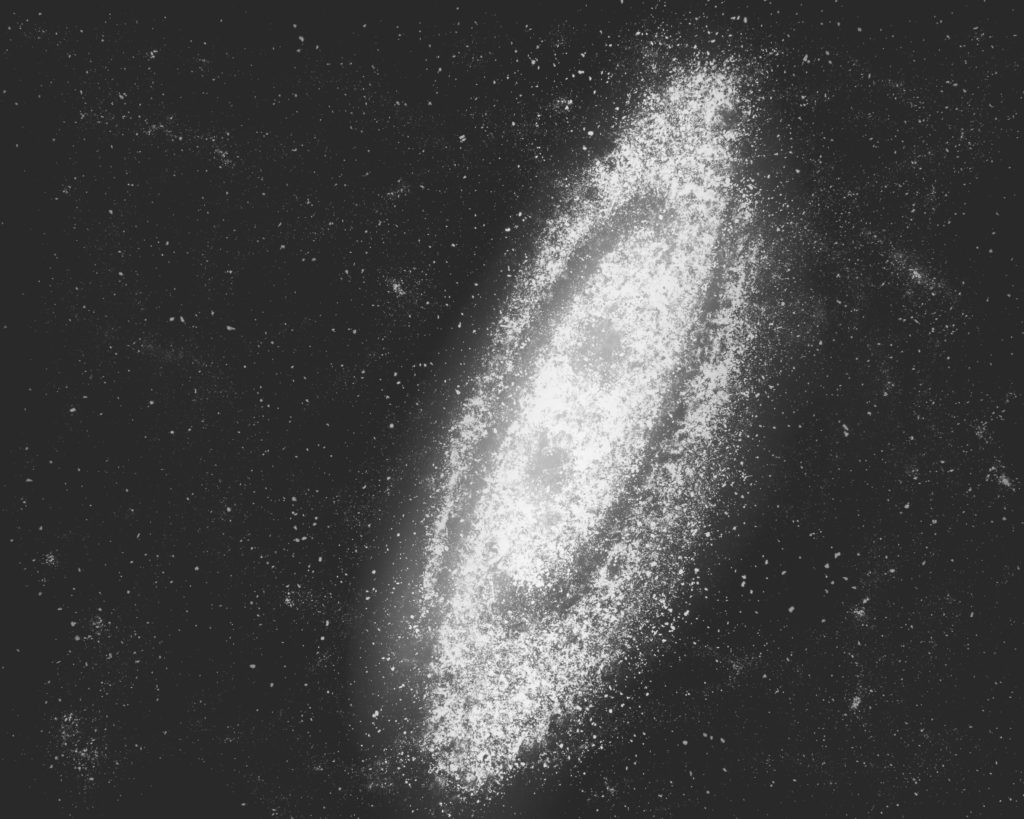

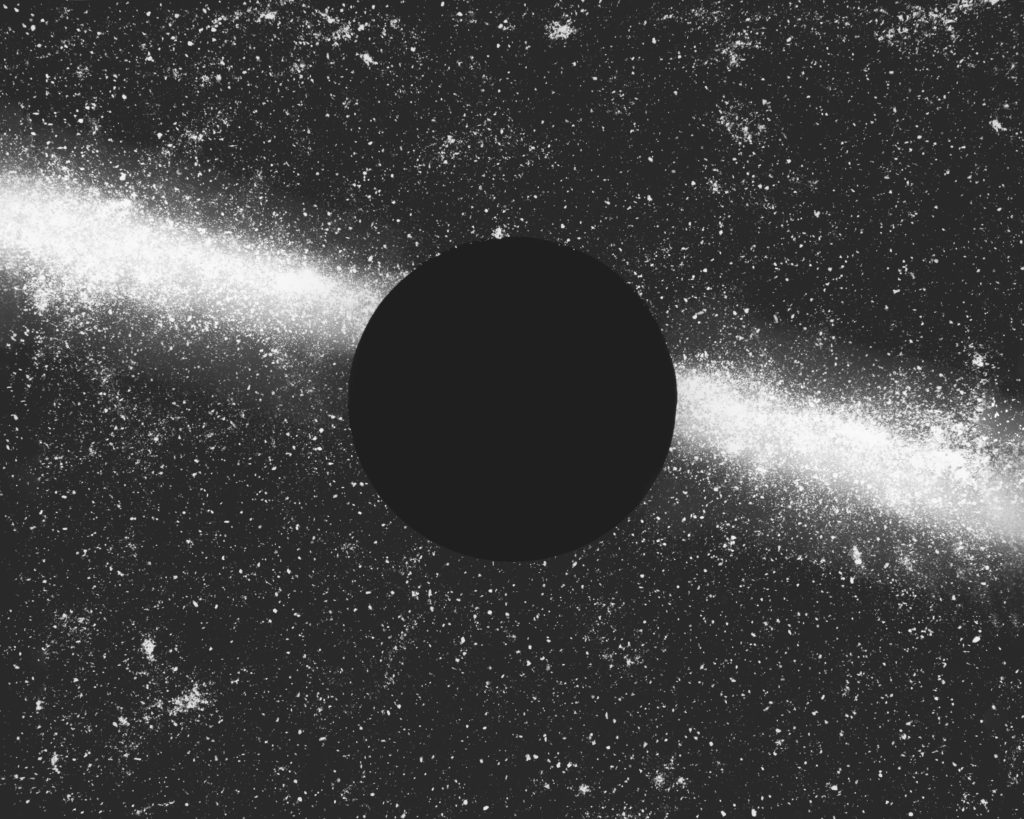

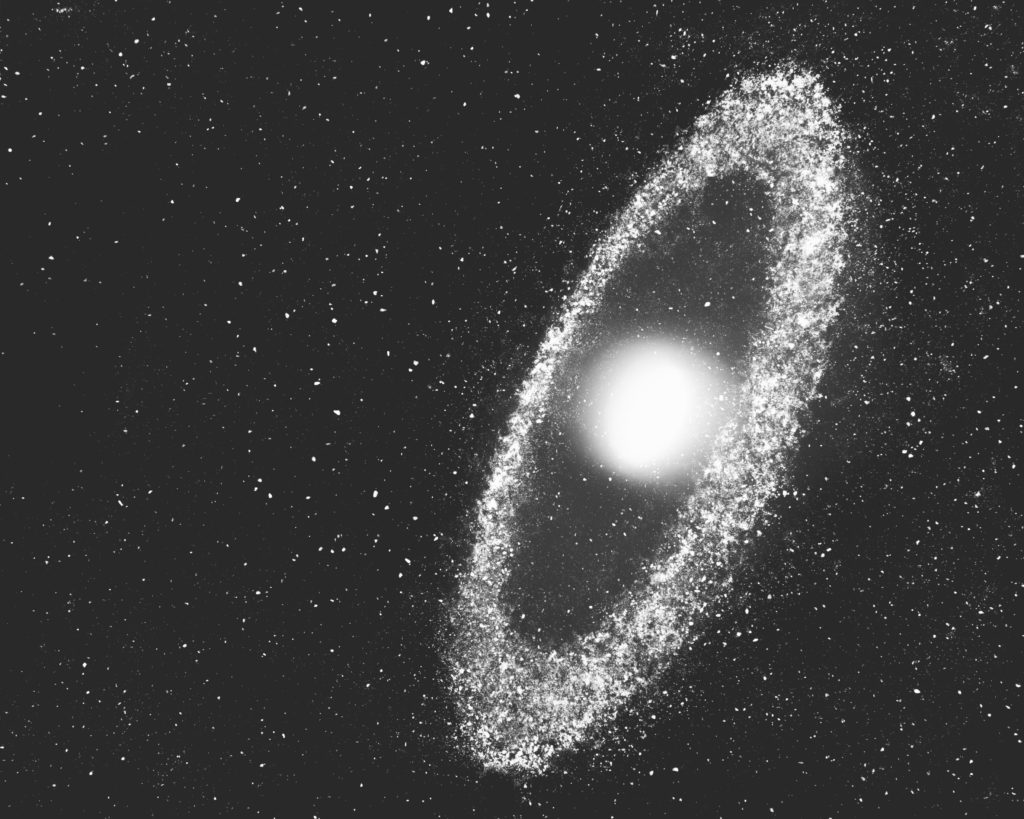

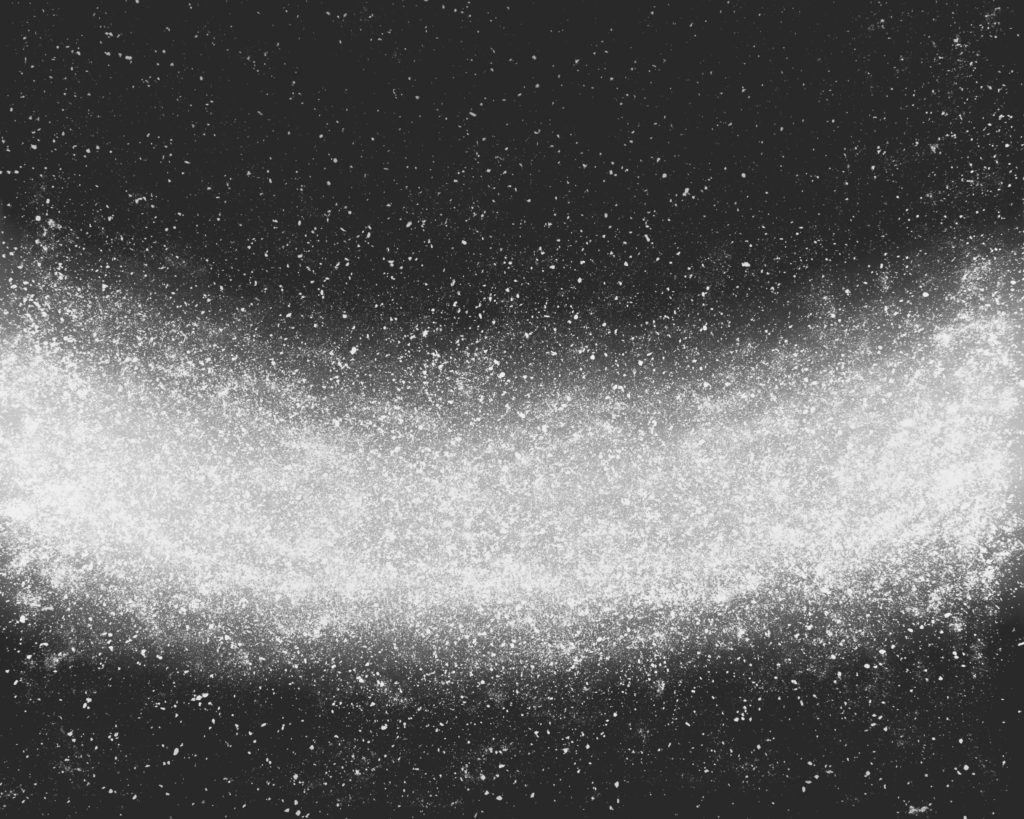

The circle of life and death is the only thing you can be certain of. It’s almost magical nature, taking us from existing somewhere in the universe to being on Earth, and then back to being a part of the infinite cosmos. Alan Knox explores this ethereal concept that “we are all derived from stardust” on a personal level. Through his body of work Universal Sympathy Knox works with his grandfather's ashes to create photograms that look like they could be images of distant galaxies. This double reading of his grandfather's life and being, and space is a beautiful portrait of the circle of life and how we are all a part of the universe.

The process was both cathartic and explorative for Knox, from the initial ideas of scattering ashes in important places to the move into photograms ,which led to emotional moments working in the darkroom. Knox seems to handle working with such a personal, and emotional subject well and with a great outcome, but this was not always the case as he explains it had its hurdles, “it was very hard for me to stand back and view the work objectively.” I caught up with Knox to find out more about the process of working with photograms, the emotional experience of working with his grandfather's ashes, and his fascination with the sublime.

How did the idea come about to create Universal Sympathy?

For over a year, I had been documenting the process of scattering my Grandfather’s ashes in places which were important to him during his life, for instance where he grew up or went on family holidays. Whilst this was a therapeutic process, as time went on, I was dissatisfied with the images and sought a more subtle way of portraying the ashes. Photograms seemed the ideal method of doing this as only the trace outline of the ash would be revealed. When I thought of scattering them on paper, I realised the dust would look like star-fields when exposed to the light. I had always been very interested in astronomy, astrology and the idea that we are all derived from stardust and from that point on, the concept and development came together very quickly.

How did the idea come about to create Universal Sympathy?

For over a year, I had been documenting the process of scattering my Grandfather’s ashes in places which were important to him during his life, for instance where he grew up or went on family holidays. Whilst this was a therapeutic process, as time went on, I was dissatisfied with the images and sought a more subtle way of portraying the ashes. Photograms seemed the ideal method of doing this as only the trace outline of the ash would be revealed. When I thought of scattering them on paper, I realised the dust would look like star-fields when exposed to the light. I had always been very interested in astronomy, astrology and the idea that we are all derived from stardust and from that point on, the concept and development came together very quickly.

Universal Sympathy is quite personal, revolving around your grandad’s ashes. Is the relationship and merging of personal life and creative work something you struggled with or found came naturally? For instance, setting boundaries and potentially removing yourself from the situation to be more critical - or perhaps the opposite?

Working alone in the darkroom on such a personal project for weeks at a time was a very emotional, at times exhausting process and initially, it was very hard for me to stand back and view the work objectively. A breakthrough came when my tutor Andy Stark at the Glasgow School of Art reminded me that every viewer could impart a personal memory of their own Grandfather in the work. Realising this gave me the confidence to continue and when necessary, stand back from my personal connection to the work. When I’ve exhibited the work in galleries and at festivals, the most rewarding feedback has come when others have told me that the work reminded them of their connection to their own my grandparents or asked me to retell stories of my Grandfather’s life.

Your work as a whole explores the sublime, what initially got you hooked on that?

The sublime in its broadest sense describes the feeling of being moved, of transitioning from one point to another, wherever or whatever that may be. With Universal Sympathy, I wanted to explore the sublime as the human journey from a primordial object of the universe, to subject on Earth and the return to objecthood in death. Part of the reason I’m fascinated in the sublime is that (true to its nature) it has encompassed so many differing meanings for philosophers, writers and artists. For Edmund Burke it was the feeling of joy filled with terror when confronted with the vastness of nature, for Kant the sublime was located in the infinite scope of the human mind beyond anything in nature, for Lacan it was the part of the self which resists any form of representation, for David Lynch, it’s the mysterious blue box in Mulholland Drive. In my practice, the sublime is found in the realisation that we are all in essence one with nature and the stars from which we are all Derived.

What is the process and experience of creating photograms like for you in comparison to using a camera? Did it pose a new set of challenges?

I found the process of creating photograms very liberating. Not having to work from a negative allowed me to approach the photograph as a painter would a canvas. During my research, I discovered that astronomers working on images released by the Hubble Telescope were inspired by the landscape paintings of the American West when composing the infinite scope of space imagery into a single frame. Likewise, painters in the sublime tradition, both romantic and modern such as Thomas Moran, Kazimir Malevich and Barnett Newman were my primary references when attempting to conjure the sublime feeling. Challenges arose when working on larger print sizes than I was normally used to. I initially tested on 10x8 paper before moving on to prints over a metre in length. Whilst such scales are in keeping with the spirit of the sublime, they could be very challenging to compose and required a lot of preparation in masking, burning etc. Since photograms require no negative, you can never be entirely sure of the composition on paper until you turn on the light and inevitably, there was a lot of trial and error when working to this scale.

Universal Sympathy is a striking and beautiful body of work that explores the sublime nature of death in relation to space. At first look without context, the viewer would not know this connection, making it a unique and accessible way of viewing death and starting healthy conversations around its place in the creative world. How do you want audiences to interact with the work and what do you want them to take away from it?

Thank you! This double reading was a very important part of the concept for me. On one level, the images can be enjoyed as readily as one might enjoy the sublime landscape of imagery from the Hubble telescope, but hopefully they offer a second reading where one discovers that through photography, you become the sublime object. Hiroshi Sugimoto describes his conception of photography: “A picture is a picture because it is a fiction. A photograph is a photograph because it appears not to be a fiction. With a photograph, the medium itself is a parody, and that parody has a surprise ending that continues ad infinitum.” Sugimoto has always been a great inspiration to me and I wanted very much for the project to have this surprise ending for the viewer approaching it for the first time.

You mentioned you are just finishing up an MA. What is next for you in your practice?

Recently I’ve been working on two projects. The first, The Memory of Deep Blue revisits the 1997 chess match between Gary Kasparov and IBM’s Deep Blue supercomputer as a series of photograms, tracing each move by Deep Blue as it marked the first defeat of a reigning world chess champion to a computer. Here, I was inspired by the recent explosion in the use of artificial intelligence in art and so wanted to revisit the history of AI from a strictly analogue standpoint.

The second project works on similar themes of loss as Universal Sympathy and explores Friedrich Nietzsche’s theory of eternal recurrence whereby he believed every life has already been lived and will be relived again after death, no more, no less. After Universal Sympathy it took me a long time to re-engage in my practice but ultimately, I think taking the space and time to reflect after a long term project can really help you clarify the aspects of photography which remain authentic to yourself and your point of view.

You can see more of Alan’s work at www.alanknoxphotography.com

Want to feature on Darwin Magazine? Submit your work to submit@darwinmagazine.co.uk

Join our community and stay tuned for updates and opportunities here - www.instagram.com/darwinmagazine/